Mix-a-Majigs

USER RESEARCH

USER TESTING

PROTOTYPING

What is Mix-a-Majigs?

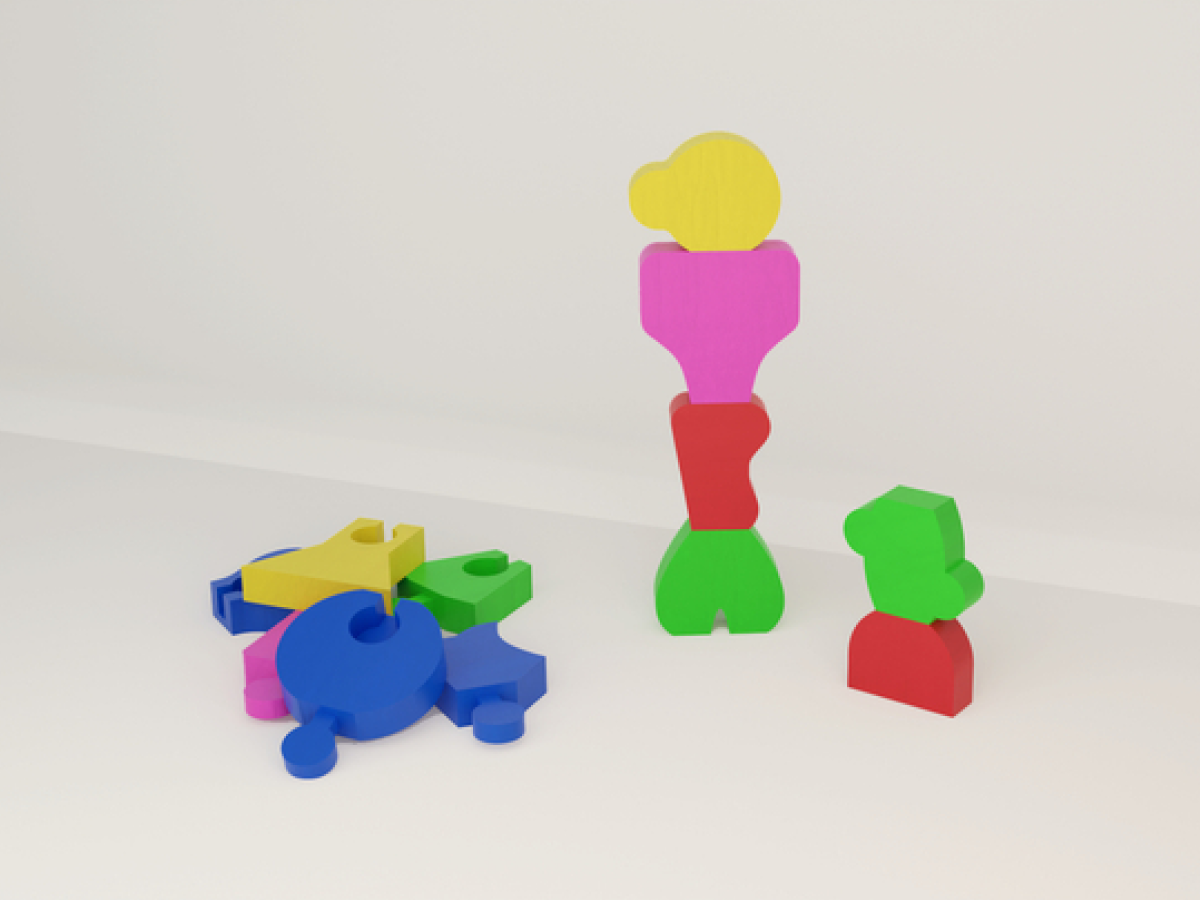

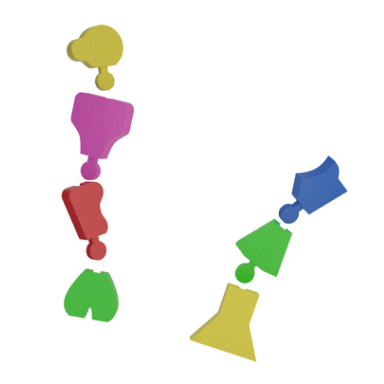

We created a toy set of puzzle-like pieces of different shapes. At its core, it resembled people, but their ambiguous shapes allowed the children

to explore creatively and role play imaginatively.

This was an effort taken with three other students through the course of 20 weeks for our Design Capstone at Stanford. In the end, we donated our

toy set to Stanford Bing Nursery— back to the children that played with it during testing.

01

User Research

We knew we wanted to design a toy for young kids, so we set out to interview children 5 years and younger, kindergarten teachers, and experts in

child development.

We spoke with each person for 30-45 minutes each, through detailed 1-on-1s. We aimed to catch subtle problems, moments of emotion, and outstanding

events for both the adult and child during play.

02

Unmet Needs

- Opportunities for open-ended play and creation, especially indoors

- Organic socio-emotional development

- Tactile ways to engage fine motor skills and spatial awareness

03

Brainstorming

We set out to create a toy that could meet both children's and teachers' needs. One of the biggest takeaways from teachers and development experts was

the success of organic play. Therefore, we established early on that we did not want another toy focused on “getting ahead”— that is, toys meant to teach

children school material instead of organic development.

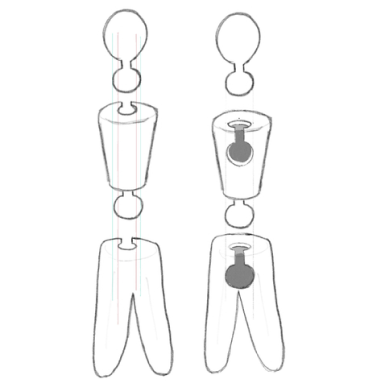

Our early concepts focused on the idea of a modular toy that could be assembled, perhaps to problem solve in groups or get creative with a LEGO-like toy.

Instead, we opted with stackable blocks that children could role play with.

04

Early Concept

These are some early sketches of shape exploration and possible connection mechanisms:

05

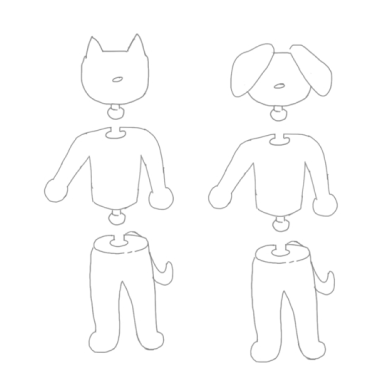

First Prototype

The first set was made of foam. Formed with just a knife and a hot wire cutter, these were very quick to produce. We created a few pieces to

mimic heads, torsos, and legs, while still being ambiguous enough for kids to interpret each piece differently.

The goal of this first prototype was to see how the kids would actually play with the toy, and if we could make improvements to the assembly of the toy.

06

First Round of Testing

With the help of a teacher at Stanford Bing Nursery, our first test was conducted on three rotations of children, ranging from 2-5 years old.

Each group consisted of 2-4 children.

The kids really seemed to the enjoy it, but the most interesting observation was what the kids made. We initially expected creations of people

they knew like family or friends, but many of them were excited to show us their “satellites” and “mermaids.”

They managed to break all the pieces during the session, which, in the toy world, is a great sign! It means the kids enjoyed it enough to wear it down.

07

What Needed to Change

- Pieces that could last for longer play sessions

- Shapes needed to be more ambiguous to get creative with

- Color! Many of the kids had specific requests

- More middle pieces for higher stacking

- More pieces in general for wider play

08

Second Round of Testing

We improved the method of construction and added more variety for the children to play with in larger groups.

This time, we were focused on individual pieces and how different ages played with the toy. Younger children struggled more with connecting the pieces,

but those that were more spatially adept would help the others learn how to put them together. We were getting even more social play in this iteration.

09

Third Prototype

Our last prototype was 3D printed. Our focus was to perfect the connections and assembly. Since the toy was made for young children, we had a lot of safety

and size constraints to take into account into the design.

We also wanted to learn how a child at home might play with the toy, whether that's solo, with a parent, or with a sibling. For the most part, we found the

same type of play as we did in previous tests, except we saw more “showing off” to the parents.

10

Final Round of Testing

We sought out to improve any fine details before our final submission. With a full set of 3D printed parts, we gave the toy to our advisor's daughter again.

She even came up with games around the toys. Her favorite was one where her father would put pieces together, close his eyes, then she'd take it apart as fast as

possible to his shock. She understood the pieces were less fragile this time, so she also helped stress test our prints. Big enough to feel sturdy, yet small enough

for a small child to hold comfortably.

11

Final Product

Mix-a-Majigs are printed from PLA, making it child-safe and easy to produce. Their universal connection means countless possibilities for creations. Promoting quick, social, and creative play, this toy will see many uses at Bing Nursery.

12

Tools & Skills Used

For Design: Fusion 360, Blender, Adobe Premiere Pro, Variety of Crafting Tools

Skills Involved: User Research, Needfinding, Design Thinking, Prototyping, User Testing, Manufacturing